Author: Ujjwal Acharya

DOI: 10.62657/cmr25opa | PDF

With research support from Umesh Shrestha, Chetana Kunwar and Pravin Bhatta of NepalFactCheck.org and editorial support from Tilak Pathak of CMR-Nepal.

Abstract

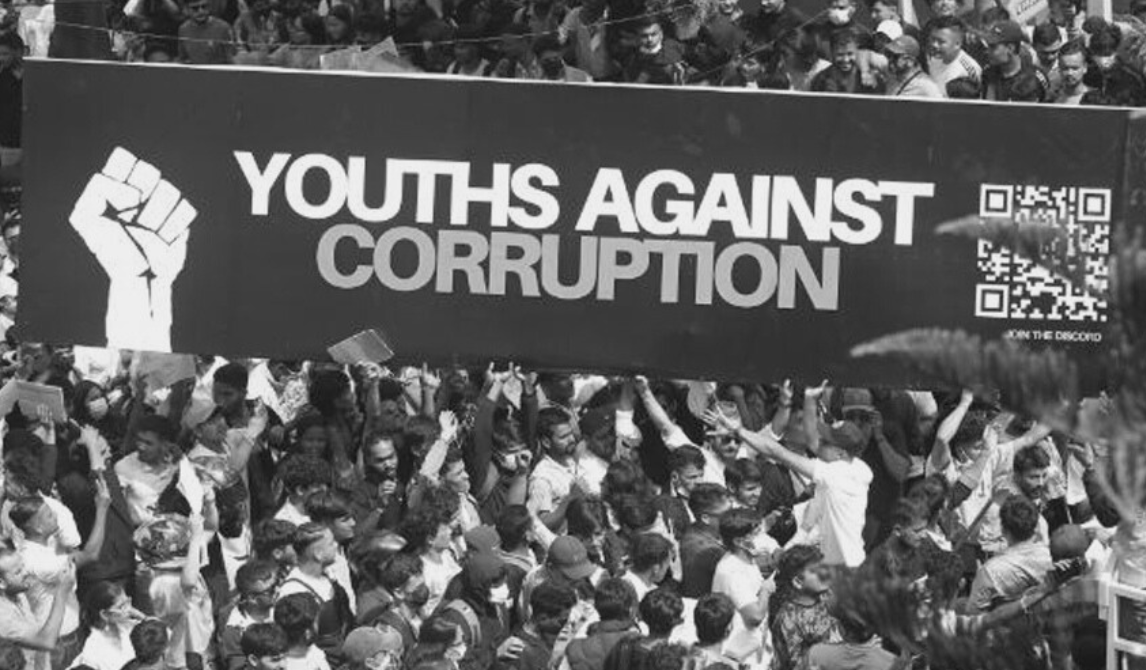

The Gen Z demonstrations in Nepal, in September 2025, was an unprecedented uprising driven by youth anger over corruption and political exclusion, triggered by a social media ban. Peaceful demonstrations escalated into violent clashes, resulting in fall of the government and the formation of an interim citizens’ government. The crisis exposed risks of misinformation, which spread rapidly across social media, fueling panic and polarization. Misinformation ranged from exaggerated death tolls to religious and political falsehoods. Fact-checkers struggled to counter emotionally charged viral claims, with even educated individuals falling prey to rumors. Key lessons learned include the need for rapid, verified official communication, prioritization of debunking malinformation by fact-checkers, closer collaboration with social media platforms, and strengthened public resilience through media and information literacy campaigns. This report recommends establishing a government crisis communication unit, increasing law enforcement transparency, scaling up media capacity and partnerships, strengthening fact-checking and launching long-term media and information literacy initiatives to combat future information disorder.

Keywords: crisis communication, misinformation, fact-checking, Gen Z protest, Nepal,

Context

On September 8, 2025, youths identifying themselves as Gen Z gathered at Maitighar, Kathmandu for a peaceful anti-corruption demonstration. What began as a peaceful demonstration quickly escalated as a group of protesters stormed the Parliament compound in New Baneshwor.[1] Security forces used heavy handed measures including tear gas, rubber bullets, and real ammunitions indiscriminately. Seventeen people were killed in Kathmandu and two more outside the Kathmandu Valley, bringing the total death toll to 19 by end of the day.[2] Everyone was shocked and stunned as the news of state repression spread and Minister for Home Affairs Ramesh Lekhak resigned on the same evening, taking moral responsibility for the deaths.[3]

On September 9, 2025, despite imposing the curfew, the state was unable to stop protests all over the nation which now were joined by thousands others angry at the government for killing youths. The day saw widespread riots. Kathmandu and other cities experienced violence on an unprecedented scale. Demonstrators burned down the Parliament, the Prime Minister’s Office, the President’s Office, the Supreme Court, the Special Court, the District Court and dozens of government buildings as well as private properties and residences owned by the political leaders and businesses of people close to political parties.[4] The rage on the day forced Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli to resign, and he was airlifted to safety by the army.[5] The ministers’ quarters were also stormed and set on fire immediately after the sitting ministers present were also airlifted to safety. Five-time former PM Sher Bahadur Deuba and his wife, the Foreign Affairs Minister Arzu Rana Deuba, faced those who stormed their residence, and were physically assaulted before they were handed over to the army.[6]

The Nepal Army took over security from 10PM on September 9 as the country slowly returned to peace.[7] The army also mediated talks with the protesters and the President resulting in appointment of Sushila Karki, Nepal’s first female Chief Justice, as the Prime Minister of the caretaker interim citizens’ government on the evening of September 12.[8] The new government swiftly dissolved the House of Representatives and is scheduled to hold the general elections on March 5, 2026.[9]

The Gen Z protest, as it is popularly known, was an unprecedented and social-media-driven movement that became a cornerstone incident in Nepal’s democratic history. However, it was not as sudden as it seemed. It was the culmination of years of frustrations among Nepal’s Gen Z youth, who were largely othered by political and social leaderships as the generation not interested in political and social matters, and only interested in migrating abroad.[10] They had witnessed and experienced bad governance, political instability, hardship in dealing with state regulations for entrepreneurship.

Nepal’s political instability added to the public frustrations. Since 2015, either of three aging leaders – Sher Bahadur Deuba of Nepali Congress, KP Sharma Oli of CPN-UML and Pushpa Kamal Dahal of Maoist Center – led seven governments, forging different equations for coalitions among each other in a political musical chair. They also stuck to the leadership within their parties, leaving no space for generational change. For example, Deuba first joined the government as the home affairs minister on May 29, 1991, and became the Prime Minister on August 23, 1995, while Oli first joined government, also as home affairs minister, on November 30, 1994, and became Deputy PM on May 2, 2006, and the PM on October 12, 2015. Similarly, Dahal first became the PM on August 22, 2008.

Nepal in past three decades has witnessed bad governance and corruption to a level that almost every citizen who had any engagement with government agencies experienced it. This experience eroded public trust in the state’s ability and willingness to deliver services to the public. Successive governments, regardless of their ideology, failed to check corruption and were non-accountable to citizens’ growing concerns. Survey findings reveal that citizens are dissatisfied with the lack of economic opportunities, rampant institutional corruption, weak governance and mass youth migration. Ineffective political leadership and subpar performance of public institutions have eroded public trust and resulted in widespread frustration at frequent government changes, political patronage and disregard for citizen voices.[11]

Development projects, even those emphasized as projects of national pride, were delayed, were subject of allegations of misappropriation of funds. Nepal’s bureaucracy and public service remain burdensome often forcing ordinary people search for intermediaries and/or pay bribe even for routine services. Bureaucratic procedures and delays became a barrier, discouraging innovation and entrepreneurship. Youth entrepreneurs found themselves obstructed by unresponsive system despite rhetorics about promoting start-ups or innovation.

Within this context, the quality of education, particularly at the university level, lagged far behind global standards, with outdated curricula, inadequate infrastructure and politicized institutions. Higher education struggled to provide students relevant skills. Taken together, these overlapping crises painted a picture of a state ignoring the needs and aspirations of its people, especially youth. Whereas the leaders and their families continued to earn successes and display a lavish lifestyle, the ordinary citizens struggled and remained helpless.

These grievances had been “boiling under the surface” for years, waiting for a trigger.

Social Media Ban as the Trigger

On September 4, 2025, The government imposed a ban on 26 social media platforms.[12] The government justified this move under a controversial directive requiring platforms to register locally which required platforms to remove government-flagged content within 24 hours or face heavy fines. The government also pointed towards a Supreme Court ruling on a contempt of court case involving an online media which directed the government to ensure registration of online platforms.[13]

For many Nepalis, especially youth, this was a direct assault on their connectivity, entrepreneurship and freedoms. In the last decade, social media had become a platform of connectivity to majority of Nepali citizens and was central to their daily lives. Only a small number of people used social media as platform of self-expression, even less to criticize government and political leaders, while a majority used it as a communication platform to remain connected with family members residing outstation or abroad and friends as well as keeping oneself updated on them. There were a sizeable number of youths who had small business that they conducted and promoted through social media, ranging from teashops to retail selling to software and web development.[14] Then there are content creators, social media influencers and their audiences who were dependent upon social media platforms. The ban struck at the heart of their social, economic and cultural engagement.

The social media ban became a hot topic for discussion in various internet-based platforms not only in well-known Facebook, X and YouTube but also in lesser-known platforms such as Reddit where the youths found out that their individual experience and frustration with the government was actually a shared experience which encouraged them to do something to change it. Another aspect that played a role in the youth’s aspiration to do something is that they were othered by the political and social leadership as a generation deep into the internet and moving abroad that they avoided political and social issues. They were potentially in a lookout to reassign their identity as a generation caring for the state. When the discussion moved to need to do something, it needed a real-time discussion platform which they found in Discord, which they used to discuss, plan and delegate responsibilities for a peaceful demonstration against corruption and political dysfunction.[15]

So, on September 8, youth groups mobilized through online networks and took to the streets. After 48 hours, Nepal saw state repression and mob violence causing 74 deaths and over 2,000 injuries as well as the political leadership kneeling down paving a way for Gen Z supported interim citizen government.

Patterns of Misinformation

The political crisis, especially due to its leaderless structure and uncalled-for state repression, was a fertile period for misinformation, disinformation, malinformation, propaganda, and hate speech, especially spreading through social media platforms.[16] There was an overwhelming volume of information which meant that correct information often gets missed with misinformation to such an extent that people don’t have the time or clarity to reflect on what’s true and what’s false.[17] The crisis was used by all threat actors, including political groups, foreign actors, partisan media, social media influencers, and extremist groups to spread disinformation supportive of their agenda and/or interest.

The misinformation observed during this period fell broadly into five categories:

- Geographic misattribution of foreign videos (e.g., Maldives, Sikkim, Karnataka videos passed off as Nepal)

- Exaggerated violence and casualty claims (e.g., Bhatbhateni skeleton claim, Parliament building death claim)

- Miscontextualised military/security activity (e.g., army vehicles video and army coup)

- Religious/cultural misinformation (e.g., Pashupatinath video, Hindu nation narrative)

- False political/leadership claims (e.g., ex-PM’s wife death, Balen Shah as PM, videos of leaders being beatn)

There were also potential malinformation that played on sensitive topics such as religion (for example: a mob trying to vandalize the Pashupatinath temple, the most revered Hindu temple; and demonstrators chanting Hindutva slogans), nationalism (for example: demonstrators chanting pro-India slogans, and foreign governments’ role) and political extremism (for example: the protest being pro-monarchy; and the army coup). Such malinformation had potentials of inciting more violence and serious unrest.

The impacts of misinformation were also partly recorded, especially through how general public responded to the misinformation on social media. There were public panic and anger as exaggerated claims of deaths and military action created fear and anxiety. There were also confusions over incidents and what’s happening as questions regarding trustworthy sources were raised by many. The distortion of protest goals where narratives were reframed to pro-monarchy and pro-Hinduism risked polarization.

A trend that was seen was misinformation was not only being shared publicly on social media but also within the closed groups, even those including opinion leaders of society.[18] A few such closed groups were monitored which indicated that even those who are considered information-literate could not escape falling victim to misinformation and in many cases sharing it. The intent may be to help, but such unverified warnings can also spark intense panic.

Another trend observed was misinformation spread in India aiming at Indian citizens to promote local political agenda also has impact in Nepal as those social media contents were also consumed in Nepal. What seemingly was an attempt to promote political positioning and ideology of certain political group in India has a more dangerous nationalistic sentiments in Nepal.

It was also noted that due to such misinformation in India, Indian fact-checking initiatives also fact-checked several viral claims, especially those relevant to them, thereby aiding efforts of Nepali fact-checkers. At NepalFactCheck.org, with limited resources and fact-checkers, it was impossible to fact-check all potential misinformation quick and effectively. Therefore, the fact-checkers focused on misinformation that carry strong elements of malinformation, and deliberately misleading content designed to cause harm and incite violence.[19] Malinformation and such narratives posed the highest risk of escalating violence at the time of crisis.

Based on the analysis of misinformation patterns during Nepal’s Gen Z protests, several critical lessons emerge for managing information disorders during political crises.

Lessons Learned for Combating Misinformation

The high number and rapid spread of misinformation during the Gen Z protests in Nepal showed that timely verified information is essential to counter misinformation. At the time when government agencies and official sources fail to provide immediate and factual information about unfolding events, there is an information vacuums which is filled by speculation, rumors and deliberately misused by the malicious actors to spread false narratives of political and other agenda.

During Gen Z protests, the state’s failure to provide real-time official updates about casualty figures and military movements created fertile ground for exaggerated claims and conspiracy theories. Citizens seeking information turned to unverified social media posts and clickbait contents. This shows the need of establishing official communication system actively monitoring rumors and providing factual information on those rumors.

It also highlighted the need of fact-checking which prioritizes emotionally charged claims, particularly those involving religion, nationalist and political sensitives. During such events, misinformation with emotional resonance such as exaggerated death tolls, false claims about attacks on religious sites or fabricated stories about political leaders spread more rapidly and had the potential to escalate tensions.

These emotionally charged narratives are not only shared widely but also pose the dangerous risk of inciting violence or deepening social divisions. The showed that fact-checking should be promoted and their limited resources must be strategically deployed to address malinformation rather than trying to debunk all misinformation.

Another crucial learning was that fact-checkers need to create a pre-agreed emergency channel with social media platforms to flag dangerous contents, so that the resources of the platforms are also mobilized to check those contents to limit spread.

Finally, the widespread circulation of misinformation among even information-literate individuals showed that media and information literacy campaigns are crucial to strengthen public resilience and are needed in a bigger scale.

The observation that misinformation was shared not only publicly but also within closed groups containing opinion leaders and educated individuals showed that traditional assumptions about promoting information literacy among vulnerable population only may be insufficient during crisis situations. It was seen that even people normally capable of analyzing information critically became vulnerable to misinformation as emotions ran high and the desire to help or warn others overrode critical thinking.

Recommendations

The government should

- establish a crisis communication unit to provide monitor rumors and provide verified updates through responsible agencies during crisis. Such unit should be responsible for disseminating accurate, timely information across multiple channels preventing information vacuums that allow misinformation.

- ensure transparency of law enforcement operations to prevent speculation that fuels conspiracy theories and rumors.

- initiate mass scale media and information literacy campaigns, including adding critical thinking and combating misinformation knowledge and skills in school curricula.

The media and fact-checkers should

- scale up fact-checking capacity during crises and distribute debunks as widely as possible across multiple platforms and formats.

- monitor misinformation narratives and focus on fact-checking malinformation.

- build collaborative partnerships to use each other’s strength to fact-check and distribute debunks.

- build relationship with social media platforms, especially their trust and safety teams, to establish direct communication channels to flag dangerous contents.

The social media platforms should

- scale up content moderation during crisis period by adding friction to viral sharing by implementing temporary measures to slow the spread of unverified content.

- display warnings about the rapidly changing situation and potential misinformation

- reduce the algorithmic promotion of content from sources other than trusted sources. However, such measures should be designed to balance free expression with harm reduction and be temporary in nature during crisis periods when misinformation poses higher risks to public safety.

- flag out of context and old media being shared through metadata and identification.

- develop partnership with and support local fact-checking initiatives to flag, identify and label misinformation.

The civil society organizations and educational institutions should

- design and implement media and information literacy interventions to all citizens.

- train opinion leaders to serve as local sources of verified information during crises.

- promote fact-checking and trusted sources of information.

Further Reading:

- Ray, Aarati (2025 September 15). How misinformation fulled panel during Gen Z uprising. The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2025/09/15/how-misinformation-fuelled-panic-during-gen-z-uprising

- Gahatraj, Diwash & Sinha, Chandrani (2025 September 18). Nepal’s Gen Z protest: How Fake News Tried to Rewrite a Revolution. Inter Press Services. https://www.ipsnews.net/2025/09/nepals-gen-z-protest-how-fake-news-tried-to-rewrite-a-revolution/

- Adhikari, Deepak (2025 September 18). How Social Media Was Flooded With False News After Nepal’s Gen Z Protests. Nepal Check. https://nepalcheck.org/2025/09/18/how-social-media-was-flooded-with-false-news-after-nepals-gen-z-protests/

[1] The Himalayan Times. (2025, September 9). Gen Z protesters enter Federal Parliament Building. https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/gen-z-protesters-enter-federal-parliament-building

[2] BBC. (2025, September 8). Nepal lifts social media ban after 19 killed in protests. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cp98n1eg443o

[3] Nepal News. (2025, September 22). Home Minister Ramesh Lekhak resigns. https://english.nepalnews.com/s/politics/home-minister-ramesh-lekhak-resigns/

[4] BBC. (2025, September 9). Nepal parliament set on fire after PM resigns over anti-corruption protests. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0m4vjwrdwgo

[5] Kathmandu Post. (2025, September 9). Prime Minister Oli resigns amid deadly protests. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2025/09/09/prime-minister-oli-resigns-amid-deadly-protests

[6] CNN. (2025, September 10). Nepal protests: After toppling the prime minister, Gen-Z protesters face an uncertain future. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/09/10/asia/nepal-protests-gen-z-outcome-intl-hnk

[7] BBC. (2025, September 9). Nepal parliament set on fire after PM resigns over anti-corruption protests. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0m4vjwrdwgo

[8] BBC. (2025, September 14). Nepal’s interim PM to hand over power within six months. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cp8wjz90z4no

[9] Al Jazeera. (2025, September 17). Who is Sushila Karki, Nepal’s new 73-year-old interim prime minister. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/17/who-is-sushila-karki-nepals-new-73-year-old-interim-prime-minister

[10] See Britannica. (2025, September 22). 2025 Nepalese Gen Z Protests. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/2025-Nepalese-Gen-Z-Protests

[11] Sapkota, P., Adhikari, S. & Pathak, T. (2025, June 26). Frustrated by leaders, not democracy. The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/columns/2025/06/26/frustrated-by-leaders-not-democracy

[12] Kathmandu Post. (2025, September 4). Nepal bans Facebook and other major social media platforms over non-compliance. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2025/09/04/nepal-bans-facebook-and-other-major-social-media-platforms-over-non-compliance

[13] Anadolu Agency. (2025, August 16). Nepal’s top court orders all social media, online sites must register. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/nepals-top-court-orders-all-social-media-online-sites-must-register/3661965

[14] See Kathmandu Post. (2025e, September 4). Nepal’s social media ban explained in six questions. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2025/09/04/nepal-s-social-media-ban-explained-in-six-questions

[15] See Al Jazeera. (2025, September 15). ‘More egalitarian’: How Nepal’s Gen Z used gaming app Discord to pick PM. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/15/more-egalitarian-how-nepals-gen-z-used-gaming-app-discord-to-pick-pm

[16] [17] [18] [19] Kathmandu Post. (2025, September 15). How misinformation fuelled panic during Gen Z uprising. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2025/09/15/how-misinformation-fuelled-panic-during-gen-z-uprising